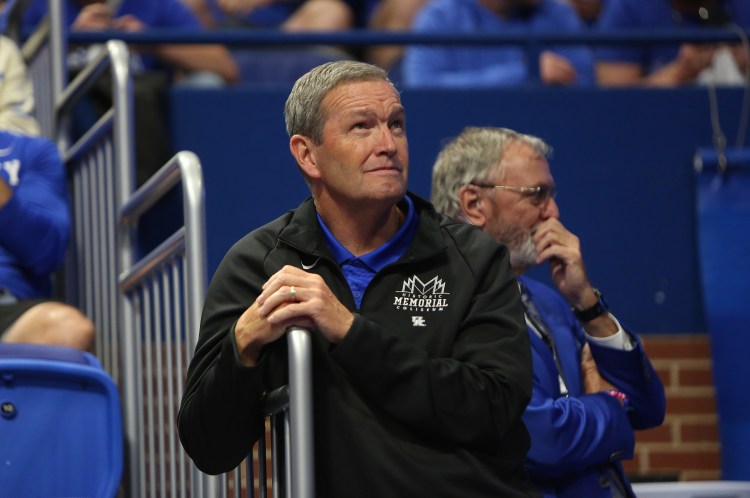

Few topics generate more emotion around Kentucky basketball right now than NIL. Recruiting misses, uncertain momentum, and growing national competition have pushed the conversation well beyond message boards and into the mainstream. That reality followed Kentucky athletic director Mitch Barnhart into Rupp Arena on Saturday night, where he addressed questions about the school’s NIL structure before the Wildcats tipped off against Indiana.

Barnhart did not shy away from the subject. Instead, he offered a detailed defense of Kentucky’s approach, one that he believes is both sustainable and competitive — even as outside pressure continues to mount, particularly around the men’s basketball program and its lack of commitments in the 2026 recruiting class.

At the heart of Barnhart’s message was a reminder that Kentucky’s NIL model was never designed to be a free-for-all. It was built, he said, on long-standing partnerships, institutional relationships, and a broader vision for how NIL should function inside one of college athletics’ most complex ecosystems.

“We’ve got some incredibly strong Kentucky partners in our network,” Barnhart said. “We do ask that we look at that and say, hey, is there a space for them to be able to work with our partners first?”

That comment, simple on the surface, speaks to the philosophical divide that continues to define NIL across college sports. While some programs operate with loosely organized collectives and open-market bidding wars, Kentucky has taken a more structured approach, prioritizing relationships that already help fund the department’s core operations — from travel and facilities to staffing and day-to-day logistics.

Barnhart’s position is clear: those partnerships matter, and they should not be discarded simply because NIL has introduced new dynamics into recruiting.

This is where much of the criticism begins.

To some fans and observers, Kentucky’s model feels cautious in an era that increasingly rewards aggression. When elite basketball recruits announce commitments elsewhere — often tied to reported NIL packages — the absence of public movement from Kentucky fuels the perception that the Wildcats are falling behind.

Barnhart pushed back on that idea directly.

At no point, he stressed, are Kentucky athletes restricted from pursuing outside NIL opportunities. The school may encourage players to explore in-house partnerships first, but it does not close the door to other options.

“There is no one-size-fits-all,” Barnhart said. “If that doesn’t work and they want to go do some other things, they absolutely have the opportunity to do that.”

That clarification matters, especially as misinformation continues to circulate about NIL restrictions at various programs. Barnhart’s message was that Kentucky’s approach is not about control — it is about alignment. The athletic department wants NIL to complement its existing infrastructure, not undermine it.

Still, the pressure is real.

Kentucky basketball operates under a microscope unlike almost any other program in the country. Recruiting is not just a function of wins and losses; it is viewed as a referendum on relevance. When the Wildcats do not land top prospects, questions quickly escalate from “why not?” to “what’s broken?”

Barnhart acknowledged that reality late in the interview, conceding that results ultimately drive perception.

“We’ve got some teams doing that incredibly well,” he said. “We’ve got a couple that are struggling, and we’ve got to get them going.”

That admission is significant. It reflects an understanding that explanations, no matter how logical, only carry so much weight without tangible success on the court.

The criticism surrounding Kentucky’s NIL structure has often centered on its partnership with JMI, a marketing and sponsorship firm that plays a role in connecting athletes with brand opportunities. Critics argue that this structure creates friction in a rapidly evolving NIL landscape, where speed, flexibility, and individualized deals are increasingly important.

Barnhart rejected the idea that JMI or Kentucky’s model limits competitiveness.

“Why in the world would we do anything other than give ourselves the best chance to win?” he said, adding that many programs nationwide operate in similar ways.

That comment speaks to a broader misunderstanding about NIL implementation. While public perception often frames NIL success solely in terms of headline-grabbing deals, much of the real work happens behind the scenes — building systems, maintaining compliance, and ensuring long-term viability.

Barnhart’s defense suggests that Kentucky views NIL as a marathon, not a sprint.

But marathons are hard to sell to a fan base accustomed to immediate results.

The frustration around the 2026 recruiting class exemplifies that tension. Kentucky’s lack of early commitments has become a talking point, particularly as rivals lock in prospects and generate momentum. In today’s recruiting culture, momentum is currency, and silence can feel like stagnation.

Barnhart did not directly address specific recruits, but his comments suggest that Kentucky remains confident in its process, even if it unfolds differently than others.

That confidence, however, exists in a rapidly shifting environment. NIL has fundamentally altered how athletes evaluate programs. Relationships still matter, but so do transparency, flexibility, and perceived alignment with player interests. Programs that fail to communicate their value clearly risk being misunderstood — or overlooked.

Kentucky’s challenge, then, is not simply about money. It is about messaging.

Barnhart’s remarks were an attempt to clarify that message. He emphasized that NIL partnerships at Kentucky do more than generate individual payouts. They support the entire athletic department, ensuring stability across sports. In his view, protecting those partnerships ultimately benefits athletes by preserving resources and infrastructure.

That argument resonates at an administrative level, but it can feel abstract to recruits making deeply personal decisions.

For a five-star basketball prospect, NIL is not an abstract concept. It is immediate. It is tangible. It is often compared side by side with other offers. Kentucky must bridge that gap — translating its long-term vision into short-term clarity for players and families.

Barnhart’s acknowledgment of outside noise suggests that the department understands this urgency.

At the same time, his comments reveal a belief that Kentucky’s brand still carries immense weight. History, exposure, development, and national relevance remain powerful selling points. NIL may have changed the rules, but it has not erased the value of tradition.

Whether that belief holds in the long run remains one of the most pressing questions facing the program.

College basketball is entering an era where balance is difficult to maintain. Programs must be aggressive without being reckless, flexible without being disorganized, and competitive without sacrificing identity. Barnhart’s defense of Kentucky’s NIL approach reflects an attempt to walk that tightrope.

Critics may argue that the Wildcats need to adapt faster. Supporters may counter that sustainability matters. The truth likely lies somewhere in between.

What is undeniable is that Kentucky basketball sits at a crossroads. Recruiting momentum, on-court results, and NIL perception are now intertwined in ways that did not exist even a few years ago. Every decision is amplified. Every explanation scrutinized.

Barnhart’s comments did not promise sweeping changes. They did not announce a dramatic shift in philosophy. Instead, they reinforced a belief in the current structure — while acknowledging that outcomes must improve.

That may not satisfy everyone, but it offers insight into how Kentucky views its place in the modern NIL era.

The pressure is not going away. Recruits will continue to compare. Fans will continue to question. Rivals will continue to push boundaries. Kentucky’s response will ultimately be measured not by statements, but by success.

For now, Barnhart has made his stance clear: Kentucky believes its NIL model c

an compete. The burden of proof, as always in Lexington, will be carried on the court.