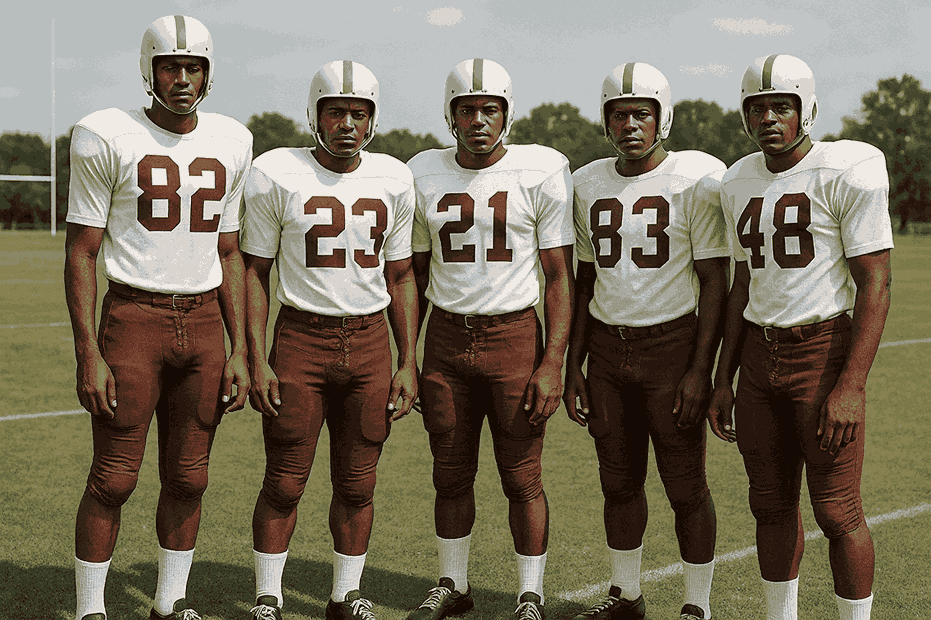

Breaking Barriers in Crimson: How Five Courageous Walk-Ons Quietly Sparked the Integration of Alabama Football in 1967—A Forgotten Chapter of Grit, Grace, and the Silent Revolution That Changed the Tide Forever

In the storied halls of Alabama football history, certain names echo across generations—Bear Bryant, Joe Namath, Derrick Thomas. Yet, buried beneath the weight of trophies and tradition lies a quieter legacy: one forged not under the blinding lights of Bryant-Denny Stadium, but on the raw practice fields of spring 1967. This is the untold story of five brave young men who changed Crimson Tide history—without fanfare, scholarships, or guarantees.

It began with Dock Rone, a freshman from Montgomery, Alabama, who walked into Coach Paul “Bear” Bryant’s office with a dream. Rone, a standout high school guard, wasn’t just asking for a shot at football—he was asking to break a barrier. He would become the first African American to wear a Crimson Tide football uniform, even if only in practice.

“I admire your courage, young man,” Bryant told Rone, granting him permission to try out if he passed the physical and met academic requirements.

On April 1, 1967, Rone stepped onto the practice field, making history. But he wasn’t alone for long. He was soon joined by four other African American students—Arthur Dunning (Mobile), Melvin Leverett (Prichard), Andrew Pernell (Bessemer), and Jerome Tucker (Birmingham). These five trailblazers became the first Black players to line up, even unofficially, for one of the most iconic and segregated programs in college football.

Though their presence was not widely publicized at the time, it marked the true beginning of integration in Alabama football—three years before Wilbur Jackson became the program’s first Black scholarship player in 1970, and four years before John Mitchell became the first African American to play in a varsity game in 1971.

According to Keith Dunnavant’s The Missing Ring, Bryant and his staff instructed the team not to treat the newcomers any differently. “We shouldn’t make a big deal about it,” said former player Tom Sommerville. “Just treat ‘em like everybody else, which we did.” While that helped ease their transition, Andrew Pernell later reflected that a sense of isolation lingered. “From the players and other coaches, it was just like… distance. It was like you didn’t exist for the most part.”

The challenges extended beyond the field. Out of nearly 12,000 students at the University of Alabama in 1967, only 300 were Black. The walk-ons didn’t live in Bryant Hall with the rest of the team due to NCAA rules restricting non-scholarship athletes from such accommodations. They trained in the same heat, hit the same drills, but remained outsiders in many ways.

Despite the odds, Rone, Pernell, and Tucker dressed out for Alabama’s A-Day intrasquad game on May 5, 1967. Rone and Tucker even saw playing time in front of 15,000 fans. At spring’s end, Rone said, “I got a fair shot. I expect to get a chance to play next season.”

But his journey was cut short. Family hardship forced Rone to leave school that summer, and he was soon drafted into military service. “I think he would have played one day,” Bryant later recalled.

Pernell returned in 1968 and played briefly in the A-Day game before a technicality involving his academic scholarship ended his football career. “I figured that was about as far as I could go with this thing,” he said.

Yet, their legacy endured.

Following their quiet rebellion against the status quo, Coach Bryant gave his staff the green light to actively recruit Black players, signaling a shift that would shape the program’s future and help transform the Southeastern Conference. Though their names may not hang in the stadium or echo on Saturdays in the fall, Dock Rone, Andrew Pernell, and their fellow walk-ons were the architects of a new era.

They didn’t do it for glory. They did it for opportunity. They did it so the next generation wouldn’t have to knock so hard on the doors they cracked open.

And in doing so, they didn’t just walk onto the fie

ld. They walked into history.